Also seeTocqueville American Experiment

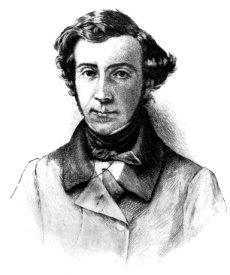

Alexis de Tocqueville

Democracy in America

In Democracy in America ( Democracy In America (The Book) in HyperText), published in 1835, Tocqueville wrote of the New World and its burgeoning democratic order. Observing from the perspective of a detached social scientist, Tocqueville wrote of his travels through America in the early 19th century when the market revolution, Western expansion, and Jacksonian democracy were radically transforming the fabric of American life. He saw democracy as an equation that balanced liberty and equality, concern for the individual as well as the community. A critic of individualism, Tocqueville thought that association, the coming together of people for common purpose, would bind Americans to an idea of nation larger than selfish desires, thus making a civil society which wasn't exclusively dependent on the state.

Tocqueville's penetrating analysis sought to understand the peculiar nature of American civic life. In describing America, he agreed with thinkers such as Aristotle, James Harrington and Montesquieu that the balance of property determined the balance of political power, but his conclusions after that differed radically from those of his predecessors. Tocqueville tried to understand why America was so different from Europe in the last throes of aristocracy. America, in contrast to the aristocratic ethic, was a society where money-making was the dominant ethic, where the common man enjoyed a level of dignity which was unprecedented, where commoners never deferred to elites, where hard work and money dominated the minds of all, and where what he described as crass individualism and market capitalism had taken root to an extraordinary degree.

The uniquely American mores and opinions, Tocqueville argued, lay in the origins of American society and derived from the peculiar social conditions that had welcomed colonists in prior centuries. Unlike Europe, venturers to America found a vast expanse of open land. Any and all who arrived could own their own land and cultivate an independent life. Sparse elites and a number of landed aristocrats existed, but, according to Tocqueville, these few stood no chance against the rapidly developing values bred by such vast land ownership. With such an open society, layered with so much opportunity, men of all sorts began working their way up in the world: industriousness became a dominant ethic, and "middling" values began taking root.

This equality of social conditions bred political and social values which determined the type of legislation passed in the colonies and later the states. By the late 18th century, democratic values which championed money-making, hard work, and individualism had eradicated, in the North, most remaining vestiges of old world aristocracy and values. Eliminating them in the South proved more difficult, for slavery had produced a landed aristocracy and web of patronage and dependence similar to the old world, which would last until the antebellum period before the Civil War.

Tocqueville asserted that the values that had triumphed in the North and were present in the South had begun to suffocate old-world ethics and social arrangements. Legislatures abolished primogenitureentails, resulting in more widely distributed land holdings. Landed elites lost the ability to pass on fortunes to single individuals. Hereditary fortunes became exceedingly difficult to secure and more people were forced to struggle for their own living.

This rapidly democratizing society, as Tocqueville understood it, had a population devoted to "middling" values which wanted to amass, through hard work, vast fortunes. Such an ethos explained, in Tocqueville's mind, why America was so different from Europe. In Europe, he claimed, nobody cared about making money. The lower classes had no hope of gaining more than minimal wealth, while the upper classes found it crass, vulgar, and unbecoming of their sort to care about something as unseemly as money; many were virtually guaranteed wealth and took it for granted. These cultural differences, identified so remarkably by Tocqueville, have led many subsequent scholars to explain that in 19th-century Europe, workers could see elites walk down the street wearing fancy attire and demand class warfare and revolution, but in America, at the same time, workers would see people fashioned in exquisite attire and merely proclaim that through hard work they too would soon possess the fortune necessary to enjoy such luxuries.

These unique American values, many have suggested, explain American exceptionalism and shed light upon many mysterious phenomena such as why America has never embraced socialism as dramatically as other leading Western countries. To Tocqueville, America was set apart by its peculiar democratic mores. But, despite maintaining, with Aristotle, More, Harrington, Montesquieu, and others that the balance of property determined the balance of power, Tocqueville argued that, as America showed, equitable property holdings did not ensure the rule of the best men. In fact, it did quite the opposite. The widespread, relatively equitable property ownership which distinguished America and determined its mores and values also explained why the American masses held elites in such contempt.

More than just imploding any traces of old-world aristocracy, ordinary Americans also refused to defer to those possessing, as Tocqueville put it, superior talent and intelligence. These natural elites, who Tocqueville asserted were the lone virtuous members of American society, could not enjoy much share in the political sphere as a result. Ordinary Americans enjoyed too much power, claimed too great a voice in the public sphere, to defer to intellectual superiors. This culture promoted a relatively pronounced equality, Tocqueville argued, but the same mores and opinions that ensured such equality also promoted, as he put it, a middling mediocrity.

Those who possessed true virtue and talent would be left with limited choices, choices which many have suggested shed light on American society today. Those with the most education and intelligence would either, Tocqueville prognosticated, join limited intellectual circles to explore the weighty and complex problems facing society which have today become the academic or contemplative realms, or use their superior talents to take advantage of America's growing obsession with money-making and amass vast fortunes in the private sector. Uniquely positioned at a crossroads in American history, Tocqueville's Democracy in America attempted to capture the essence of American culture and values.

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.